Proposing SQL Statement Coverage Metrics: Difference between revisions

Programsam (talk | contribs) |

Programsam (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 439: | Line 439: | ||

# http://works.dgic.co.jp/djunit/ | # http://works.dgic.co.jp/djunit/ | ||

# For our case study, we used MySQL v5.0.45-community-nt found at http://www.mysql.com/ | # For our case study, we used MySQL v5.0.45-community-nt found at http://www.mysql.com/ | ||

[[Category:Workshop Papers]] | |||

Revision as of 23:08, 14 March 2013

B. Smith, Y. Shin, and L. Williams, "Proposing SQL Statement Coverage Metrics", Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop on Software Engineering for Secure Systems (SESS 2008), co-located with ICSE, pp. 49-56, 2008.

Abstract

An increasing number of cyber attacks are occurring at the application layer when attackers use malicious input. These input validation vulnerabilities can be exploited by (among others) SQL injection, cross site scripting, and buffer overflow attacks. Statement coverage and similar test adequacy metrics have historically been used to assess the level of functional and unit testing which has been performed on an application. However, these currently-available metrics do not highlight how well the system protects itself through validation. In this paper, we propose two SQL injection input validation testing adequacy metrics: target statement coverage and input variable coverage. A test suite which satisfies both adequacy criteria can be leveraged as a solid foundation for input validation scanning with a blacklist. To determine whether it is feasible to calculate values for our two metrics, we perform a case study on a web healthcare application and discuss some issues in implementation we have encountered. We find that the web healthcare application scored 96.7% target statement coverage and 98.5% input variable coverage

1. Introduction

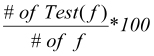

According to the National Vulnerability Database (NVD)1, more than half of all of the ever-increasing number of cyber vulnerabilities reported in 2002-2006 were input validation vulnerabilities. As Figure 1 shows, the number of input validation vulnerabilities is still increasing.

Figure 1. NVD's reported cyber vulnerabilities2

Figure 1 illustrates the number of reported instances of each type of cyber vulnerability listed in the series legend for each year displayed in the x-axis. The curve with the square shaped points is the sum of all reported vulnerabilities that fall into the categories “SQL injection”, “XSS”, or “buffer overflow” when querying the National Vulnerability Database. The curve with diamond shaped points represents all cyber vulnerabilities reported for the year in the x-axis. For several years now, the number of reported input validation vulnerabilities has been half the total number of reported vulnerabilities. Additionally, the graph demonstrates that these curves are monotonically increasing; indicating that we are unlikely to see a drop in the future in ratio of reported input validation vulnerabilities.

Input validation testing is the process of writing and running test cases to investigate how a system responds to malicious input with the intention of using tests to mitigate the risk of a security threat. Input validation testing can increase confidence that input validation has been properly implemented. The goal of input validation testing is to check whether input is validated against constraints given for the input. Input validation testing should test both whether legal input is accepted, and whether illegal input is rejected. A coverage metric can quantify the extent to which this goal has been met. Various coverage criteria have been defined based on the target of testing (specification or program as a target) and underlying testing methods (structural, fault-based and error-based)[19]. Statement coverage and branch coverage are well-known program-based structural coverage criteria[19].

However, current structural coverage metrics and the tools which implement them do not provide specific information about insufficient or missing input validation. New coverage criteria to measure the adequacy of input validation testing can be used to highlight a level of security testing. Our research objective is to propose and to validate two input validation testing adequacy metrics related to SQL injection vulnerabilities. Our current input validation coverage criteria consist of two experimental metrics: input variable coverage, which measures the percentage of input variables used in at least one test; and target statement coverage, which measures the percentage of SQL statements executed in at least one test.

An input variable is any dynamic, user-assigned variable which an attacker could manipulate to send malicious input to the system. In the context of the Web, any field on a web form is an input variable as well as any number of other client-side input spaces. Within the context of SQL injection attacks, input variables are any variable which is sent to the database management system, as will be illustrated in further detail in Section 2. A target statement is any statement in an application which is subject to attack via malicious input; for this paper, our target statements will be all SQL statements found in production code. Other input sources can be leveraged to form an attack, but we have chosen not to focus on them for this study because they comprise less than half of recently reported cyber vulnerabilities (see Figure 1 and explanation).

In practice, even software development teams who use metrics such as traditional statement coverage often do not achieve 100% values in these metrics before production[1]. If the lines left uncovered contain target statements, traditional statement coverage could be very high while little to no input validation testing is performed on the system. A target statement or input variable which is involved in at least one test might achieve high input validation coverage metrics yet still remain insecure if the test case(s) did not utilize a malicious form of input. However, a system with a high score in the metrics we define has a foundation for thorough input validation testing. Testers can relatively easily reuse existing test cases with multiple forms of good and malicious input. Our vision is to automate such reuse.

We evaluated our metrics on the server-side code of a Java Server Pages web healthcare application that had an extensive set of JUnit3 test cases. We manually counted the number of input variables and SQL statements found in this system and dynamically recorded how many of these statements and variables are used in executing a given test set. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: First, Section 2 defines SQL injection attacks. Then, Section 3 introduces our experimental metrics. Section 4 provides a brief summary of related work. Next, Section 5 describes our case study and application of our technique. Section 6 reports the results of our study and discusses their implications. Then, Section 7 illustrates some limitations on our technique and our metrics. Finally, Section 8 concludes and discusses the future use and development of our metrics.

2. Background

Section 2.1 explains the fundamental difference between traditional testing and security testing. Then, Section 2.2 describes SQL injection.

2.1 Testing for Security

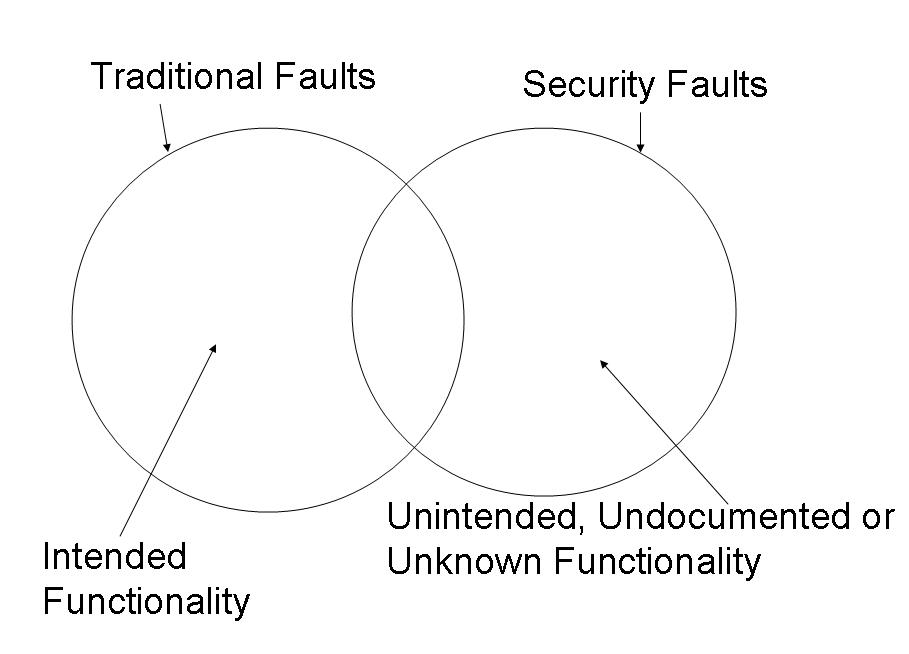

Web applications are inherently insecure[15] and web applications’ attackers look the same as any other customer to the server[12]. Developers should, but typically do not, focus on building security into web applications [6]. Security has been added to the list of web application quality criteria[11] and the result is that companies have begun to incorporate security testing (including input validation testing) into their development methodologies[3]. Security testing is contrasted from traditional testing, as illustrated by Figure 2: Functional vs. Security Testing, adapted from[17].

Represented by the left-hand circle in Figure 2, the current software development paradigm includes a list of testing strategies to ensure the correctness of an application in functionality and usability as indicated by a requirements specification. With respect to intended correctness, verification typically entails creating test cases designed to discover faults by causing failures. Oracles tell us what the system should do and failures tell us that the system does not do what it is supposed to do. The right-hand circle in Figure 2 indicates that we validate not only that the system does what it should, but also that the system does not do what it should not: the right-hand circle represents a failure occurring in the system which causes a security problem. The circles intersect because some intended functionality can cause indirect vulnerabilities because privacy and security were not considered in designing the required functionality[17]. Testing for functionality only validates that the application achieves what was written in the requirements specification. Testing for security validates that the application prevents undesirable security risks from occurring, even when the nature of this functionality is spread across several modules and might be due to an oversight in the application’s design. To adapt to the new paradigm, companies have started to incorporate new techniques. Some companies use vulnerability scanners, which behave like a hacker to make automated attempts at gaining access or misusing the system to discover its flaws[4]. A blacklist is a representative or comprehensive set of all input validation attacks of a given type (such as SQL injection, see Section 2.2). These vulnerability scanners typically use a blacklist to test potential vulnerabilities against all attacks (or a set of representative attacks). Coverage criteria for target statements can help companies assess how much of their system has the framework for a range of input validation testing. A vulnerability scanner is ineffective if its blacklist is not tested against every target statement in the system.

2.2 SQL Injection Attacks

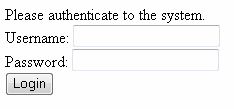

A SQL injection attack is performed when a user exploits a lack of input validation to force unintended system behavior by altering the logical structure of a SQL statement with special characters. The lack of input validation to prevent SQL injection attacks is known as a SQL injection vulnerability[2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 13-16]. Our example of this type of input validation vulnerability begins with the login form presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Example login form

Usernames typically consist of alphanumeric characters, underscores, periods and dashes. Passwords also typically consist of these character ranges and additionally allow for some other non-alphanumeric characters such as $, ^ or #. The authentication mechanism functions by a code segment resembling the one in Figure 4. Assume there exists some table maintaining a list of all usernames, passwords, and most likely some indication of the role of each unique username.

//for simplicity, this example is given in PHP. //first, extract the input values from the form $username = $_POST[‘username’]; $password = $_POST[‘password’]; //query the database for a user with username/pw $result = mysql_query(“select * from users where username = ‘$username’ AND password = ‘$password’”); //extract the first row of the resultset $firstresult = mysql_fetch_array($result); //extract the “role” column from the result $role = $firstresult[‘role’]; //set a cookie for the user with their role setcookie(“userrole”, $role);

The code in Figure 4 performs the following. First, query the database for every entry with the entered username and password. Typically, we use the first row of returned SQL results (which is retrieved by mysql_fetch_array and stored in $firstresult) because the web application (or the database management system) will ensure that there are no duplicate usernames and will ensure that every user name is given the appropriate role. Finally, we

extract the role field from the first result and give the user a cookie4, which allows the login to be persistent (i.e., the user does not have to login to view every protected page).

The example we have presented in Figure 4 performs no input validation, and as a result the example contains at least three input validation vulnerability locations. The first two are the username and password fields as given in the web form in Figure 3. An attacker could cause the code fragment change shown in Figure 5 simply by entering the SQL command fragment “‘ OR 1=1 -- AND" in the input field instead of any valid user name in Figure

3.

//from Figure 4; original code $result = mysql_query(“select * from users where username = '$username’ AND password = ‘$password’”); //code with inserted attack parameters $result = mysql_query(“select * from users where username = ‘’ OR 1=1 -- AND password = ‘PASSWORD’”);

The single quotation mark (') indicates to the SQL parser that the character sequence for the username column is closed, the fragment OR 1=1 is interpreted as always true, and the hyphens (--) tells the parser that the SQL command is over and the fragment of the query after the hyphens is a comment. With these values, the $result variable contains a list of every user in the table (and their associated role) because the where clause is always true. The first listing returned from the database is unknown and will vary based on the database configuration. Regardless, the role of the user in the first returned row will be extracted and assigned to a cookie on the attacker’s machine. The consequence is as follows: Assuming the attacker is not a registered user of the system, he or she has just been granted unauthorized access to the system with the role (and identity) associated with the first username in the table. The password field shown in Figure 3 is also vulnerable, but we do not demonstrate this attack for space reasons. Because no input validation was performed, the system can be exploited for a use that was unintended by its developers.

The exploitation of the third vulnerability requires slightly more work than the first two, but is more threatening. Presumably, the developer of this example web application provides different content to a given web user (or provides no content at all) depending on the role parameter, which is stored in a cookie. An example code for the design decision of using a cookie is Figure 6.

The $_COOKIE[‘role’] macro extracts the value stored on the user’s machine for the parameter passed (in this case “role”). The web application provides one set of content for users with the administrator role and another set of content for those with the employee role. If the role parameter is anything else, the user is redirected to authrequired.html, which presumably contains some type of message to the user that authentication is required to access the requested page. The vulnerability stems from the relatively well-known fact that HTTP cookies are usually stored in a text file on the user’s machine. In this case, the attacker need only to edit this file and see that there is a parameter named “role” and a reasonable guess for the authentication value would be “admin”. The consequence is as follows: If the attacker succeeds in guessing the correct value, the system provides content to a user who was unauthorized to view it and the system has been exploited.

if ($_COOKIE[‘role’] == ‘admin’)

{

//give admin access

}

else if ($_COOKIE[‘role’] == ‘employee’)

{

//give employee access

}

else

{

//no role or unrecognizable role,

//redirect to an error page.

header(“Location: authrequired.html”);

}

A countermeasure for the form input field vulnerability is simply to escape all control characters (such as ‘ or #) from the input variables. For the cookie vulnerability, a countermeasure would be to dynamically generate a unique identifier for the current session and store that in the cookie as well as the associated user role. Because these vulnerabilities can be prevented with input validation, they are known as input validation vulnerabilities. Figure 6 is not a SQL injection attack; however it still represents an input validation vulnerability. We have included it here in the interest of completeness, but we will not focus on this type of vulnerability in the rest of this paper.

Although a number of techniques exist to mitigate the risks posed by SQL injection vulnerabilities[2, 6, 8, 9, 13, 14], none of these techniques propose a methodology of adequacy as ensured by measuring how many commands issued to a database management system are tested by the test suite.

3. Coverage Criteria

We define two criteria for input validation testing coverage. Client-side input validation can be bypassed by attackers [7]. Therefore, we only measure the coverage of server-side code. The followings are basic terms to be used to define input validation coverage criteria.

- Target statement: A target statement (within our context) is a SQL statement which could cause a security problem when malicious input is used. For example, consider the statement

java.sql.Statement.executeQuery(String sql)

A SQL injection attack can happen when an attacker uses maliciously-devised input as explained in Section 2. Let T be the set of all the SQL statements in an application.

- Input variable: An input variable is any variable in the serverside production code which is dynamically user-assigned and sent to the database management system. Let F represent the set of all input variables in all SQL statements occurring in the production code.

3.1 Target Statement Coverage

Target statement coverage measures the percentage of SQL statements executed at least once during execution of the test suite.

Definition: A set of input validation tests satisfies target statement coverage if and only if for every SQL statement t ∈ T, there exists at least one test in the input validation test cases which executes t.

Metric: The target statement coverage criterion can be measured by the percentage of SQL statements tested at least once by the test set out of total SQL statements.

Server-side target statement coverage =

where Test(t) is a SQL statement tested at least once.

Coverage interpretation: A low value for target statement coverage indicates that testing was insufficient. Programmers need to add more test cases to the input validation set for untested SQL statements to improve target statement coverage.

3.2 Input Variable Coverage

Input variable coverage measures the percentage of input variables used in at least one test at the server-side. Input variable coverage does not consider all the constraints for the input variable.

Definition: A set of tests satisfies input variable coverage criterion if and only if for every input variable f ∈ F, there exists at least one test that uses that input variable at least once.

Metric: The input variable coverage criterion can be measured by the percentage of input variables tested at least once by the test set out of total number of input variables found in any target statement in the production code of the system.

where Test(f) is an input variable used in at least one test.

Coverage interpretation: A low value for input variable coverage indicates that input validation testing is insufficient. Programmers need to add more test cases for untested input variables to improve input variable coverage.

We note here that a test set which achieves 100% input variable coverage and 100% target statement coverage may not contain any tests with malicious input. Consider a test set which satisfies both coverage criteria and leverages a blacklist to test for input validation attacks. This test set ensures that every input variable in every target statement is tested with every attack in the blacklist.

The relationship between target statement coverage and input variable coverage is not yet known; however, we contend that input variable coverage is a useful, finer-grained measurement.

Input variable coverage has the effect of weighting a target statement which has more input variables more heavily. Since most input variables are each a separate potential vulnerability if not adequately validated, a target statement which contains more input variables is of a higher threat level.

4. Related Work

Halfrond and Orso[7] introduce an approach for evaluating the number of database interaction points which have been tested within a system. Database interaction points are similar to target statements in that they are defined by Halfrond and Orso as any statement in the application code where a SQL command is issued to a relational database management system. These authors chose to focus on dynamically-generated queries, and define a command form as a single grammatically distinct structure for a SQL query which the application under test can generate. Using their tool DITTO on an example application, Halfrond and Orso demonstrate that it is feasible to perform automated instrumentation on source code to gather command form coverage, which is expressed as the number of covered command forms divided by the total number of possible command forms.

Willmor and Embury[18] assess database coverage in the sense of whether the output received from the relational database system itself is correct and whether the database is structured correctly. The authors contend that the view of one system to one database is too simplistic; the research community has yet to consider the effect of incorrect database behavior on multiple concurrent applications or when using multiple database systems. The authors define the All Database Operations criteria as being satisfied when every database operation, which exists as a control graph node in the system under test, is executed by the test set in question.

5. Case Study

Research Question: Is it possible to manually instrument an application which interacts with a database, marking each target statement and input variable, and then dynamically gather the number of target statements executed by a test set?

To test answer our research question, we performed a case study on iTrust5, an open source web application designed for storing and distributing healthcare records in a secure manner. Section 5.1 describes the architecture and implementation specifics of iTrust. Then, Section 5.2 gives more information about how our case study was conducted.

5.1 iTrust

iTrust is a web application which is written in Java, web-based, and stores medical records for patients for use by healthcare professionals. Code metrics for iTrust Fall 2007 can be found in Table 1. The intent of the system is to be compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act6 privacy standard, which ensures that medical records be accessible only by authorized persons. Since 2005, iTrust has been developed and maintained by teams of graduate students in North Carolina State University who have used the application as a part of their Software Reliability and Testing coursework or for research purposes. As such, students were required in their assignments to have high statement coverage, as measured via the djUnit7 coverage tool.

| Package | Java Class | LoC | Statements | Methods | Variables | Test Cases | Line Coverage |

| edu.ncsu.csc.itrust.dao.mysql | AccessDAO | 156 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 12 | 100% |

| AllergyDAO | 61 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 100% | |

| AuthDAO | 184 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 23 | 98% | |

| BkpStandardsDAO | 61 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0% | |

| CPTCodesDAO | 123 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 100% | |

| EpidemicDAO | 141 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 100% | |

| FamilyDAO | 112 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 100% | |

| HealthRecordsDAO | 65 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 100% | |

| HospitalsDAO | 180 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 18 | 88% | |

| ICDCodesDAO | 123 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 100% | |

| NDCodesDAO | 122 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 100% | |

| OfficeVisitDAO | 362 | 15 | 20 | 6 | 30 | 99% | |

| PatientDAO | 322 | 14 | 15 | 4 | 38 | 100% | |

| PersonnelDAO | 196 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 15 | 100% | |

| RiskDAO | 126 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 100% | |

| TransactionDAO | 135 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 93% | |

| VisitRemindersDAO | 166 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 100% | |

| edu.ncsu.csc.itrust.dao | DBUtil | 29 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 69% |

| DAO Classes: 20 Total | 2378 | 93 | 125 | 40 | 196 | 92% |

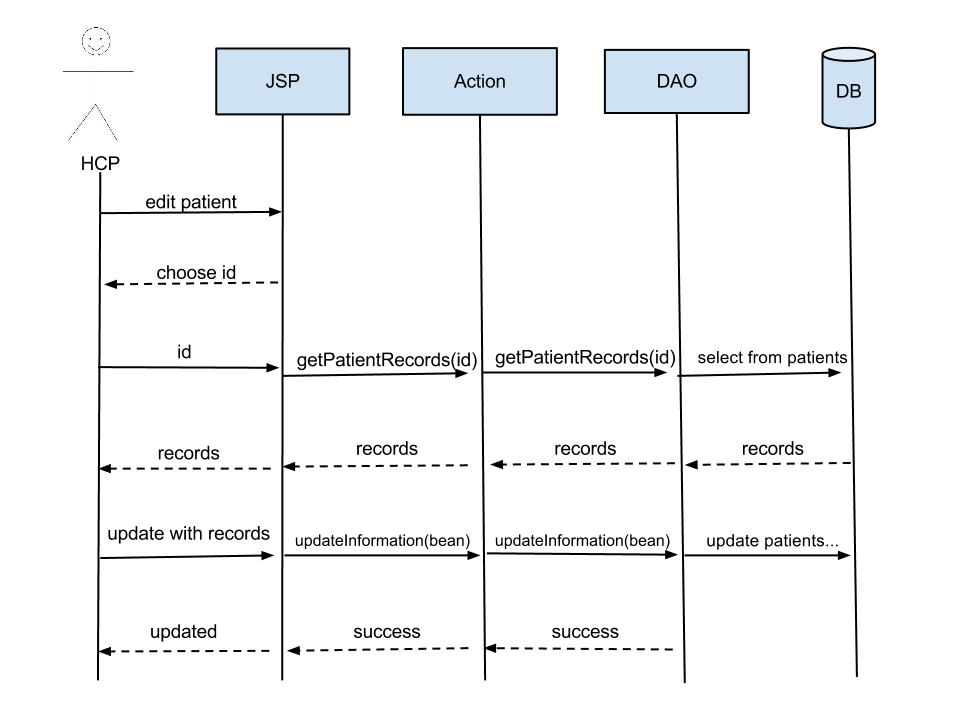

In a recent refactoring effort, the iTrust architecture has been formulated to follow a paradigm of Action and Database Access Object (DAO) stereotypes. As shown in Figure 7, iTrust contains JSPs which are the dynamic web pages served to the client. In general, each JSP corresponds to an Action class, which allows the authorized user to view or modify various records contained in the iTrust system. While the Action class provides the logic for ensuring the current user is authorized to view a given set of records, the DAO provides a modular wrapper for the database. Each DAO corresponds to a certain related set of data types, such as Office Visits, Allergies or Health Records. Because of this architecture, every SQL statement used in the production code of iTrust exists in a DAO. iTrust testing is conducted using JUnit v3.0 test cases which make calls either to the Action classes or the DAO classes. Since we are interested in how much testing was performed on the aspects of the system which interact directly with the database, we focus on the DAO classes for this study.

iTrust was written to conform to a MySQL8 back-end. The MySQL JDBC connector was used to implement the data storage for the web application by connecting to a remotely executing instance of MySQL v5.1.11-remote-nt. The java.sql.PreparedStatement class is one way of representing SQL statements in the JDBC framework. Statement objects contain a series of overloaded methods all beginning with the word execute: execute(…), executeQuery(…), executeUpdate(…), and executeBatch(). These methods are the java.sql way of issuing commands to the database and each of them represents a potential change to the database. These method calls, which we have previously introduced as target statements, are the focus of our coverage metrics.

Figure 7. General iTrust architecture

The version of iTrust we used for this study is referred to as iTrust Fall 2007, named by the year and semester it was built and redistributed to a new set of graduate students. iTrust was written to execute in Java 1.6 and thus our testing was conducted with the corresponding JRE. Code instrumentation and testing were conducted in Eclipse v3.3 Europa on an IBM Lenovo T61p running Windows Vista Ultimate with a 2.40Ghz Intel Core Duo and 2 GB of RAM.

5.2 Study Setup

The primary challenge in collecting both of our proposed metrics is that there is currently no static tool which can integrate with the test harness JUnit to determine when SQL statements found within the code have been executed. As a result, we computed our metrics manually and via code instrumentation.

The code fragment in Figure 8 demonstrates the execution of a SQL statement found within an iTrust DAO. Each of the JDBC execute method calls represents communication with the DBMS and has the potential to change the database.

We assign each execute method call a unique identifier id in the range 1, 2, ... , n where n is the total number of execute method calls. We then instrument the code to contain a call to SQLMarker.mark(id). This SQLMarker class interfaces with a research database we have setup to hold status information foreach statically identified execute method call. Before running the test suite, we load (or reload) a SQL table with records corresponding to each unique identifier from 1 to n. These records all contain a field marked which is set to false. The SQLMarker.mark(id) method changes marked to true. If marked is already true, it will remain true.

Using this technique, we can monitor the call status of each execute statement found within the iTrust production code. When the test suite is done executing, the table in our research database will contain n unique records which correspond to each method call in the iTrust production code. Each record will contain a boolean flag indicating whether the statement was called during test suite execution. The line with the comment instrumentation shows how this method is implemented in the example code in Figure 8.

java.sql.Connection conn = factory.getConnection();

java.sql.PreparedStatement ps = conn.prepareStatement("UPDATE globalVariables set SET VALUE = ? WHERE Name = ‘Timeout’;");

ps.setInt(1, mins);

SQLMarker.mark(1, 1); //instrumentation

java.sql.ResultSet rs = ps.executeQuery();

SQLMarker.mark is always placed immediately before the call to the execute SQL query (or target statement) so the method's execution will be recorded even if the statement throws an exception during its execution. There are issues in making the determination of the number of SQL statements actually possible in the production code; these will be addressed in Section 7.

To calculate input variable coverage, we included a second variable in the SQLMarker.mark method which allows us to record the number of input variables which were set in the execute method. Initially, the input variable records of each execute method are set to zero, and the SQLMarker.mark method sets them to the passed value. iTrust uses PreparedStatements for its SQL statements and as Figure 8 demonstrates, the number of input variables is always clearly visible in the production code because PreparedStatements require the explicit setting of each variable included in the statement. As with the determination of SQL statements, there are similar issues with determining the number of SQL input variables which we present in Section 7.

6. Results and Discussion

We found that 90 of the 93 SQL statements in the iTrust serverside production code were executed by the test suite, yielding a SQL statement coverage score of 96.7%. We found that 209 of the 212 SQL input variables found in the iTrust back-end were executed by the test suite, yielding a SQL variable coverage score of 98.5%. We find that iTrust is a very testable system with respect to SQL statement coverage, because each SQL statement, in essence, is embodied within a method of a DAO. This architectural decision is designed to allow the separation of concerns. For example the action of editing a patient’s records via user interface is separated from the action of actually updating that patient’s records in the database. We find that even though the refactoring of iTrust was intended to produce this high testability, there are still untested SQL statements within the production code. The Action classes of the iTrust framework represent procedures the client can perform with proper authorization. Since iTrust’s line coverage is at 91%, the results for iTrust are actually better than they would be for many existing systems due to its high testability.

The three uncovered SQL statements occurred in methods which were never called by any Action class and thus are never used in production. Two of the statements related to the management of hospitals and one statement offered an alternate way of managing procedural and diagnosis codes. The uncovered statements certainly could have eventually been used by new features added to the production and thus the fact that they are not executed by any test is still pertinent.

7. Limitations

Certain facets of the JDBC framework and of SQL in general make it difficult to establish a denominator for the ratio described for each of our coverage metrics. For example, remember that in calculating SQL statement coverage, we must find, mark and count each statically occurring SQL statement within the production code. The fragment presented in Figure 9 contains Java batch SQL statements. Similar to batch mode in MySQL, each statement is pushed into a single batch statement and then the statements are all executed with one commit. Batch statements can be used to increase efficiency or to help manage concurrency. We can count the number of executed SQL statements in a batch: a dummy variable could be instrumented within the for loop demonstrated in Figure 9 which increments each time a batch statement is added (e.g., ps.addBatch()). How many SQL statements are possible, though? The numerator will always be the same as the number of DiagnosisBeans in the variable updateDiagnoses. These beans are parsed from input the user passes to the Action class via the JSP to make changes to several records in one web form submission. The denominator is potentially infinite, however.

Additionally, the students who have worked on iTrust were required to use PreparedStatements, which elevates our resultant input variable coverage because PreparedStatements require explicit assignment to each input variable, and this may not be the case with other SQL connection methodologies. Furthermore, our metrics do not give any indication of how many input values have been tested in each input variable in each target statement.

This technique is currently only applicable to Java code which implements a JDBC interface and uses PreparedStatements to interact with a SQL database management system. Finally, we recognize that much legacy code is implemented using dynamically generated SQL queries and while our metric for target statement coverage could be applied, our metric for input variable coverage does not contain an adequate definition for counting the input variables in a dynamically generated query. Our approach will be repeatable and can generalize to other applications matching the above restrictions.

public void updateDiscretionaryAccess(List<DiagnosisBean> updateDiagnoses)

{

java.sql.Connection conn = factory.getConnection();

java.sql.PreparedStatement ps = conn.prepareStatement("UPDATE OVDiagnosis SET

DiscretionaryAccess=? WHERE ID=?");

for (DiagnosisBean d : updateDiagnoses) {

ps.setBoolean(1, d.isDiscretionaryAccess());

ps.setLong(2, d.getOvDiagnosisID());

ps.addBatch();

}

SQLMarker.mark(1, 2);

ps.executeBatch();

}

8. Conclusions and Future Work

We have shown that a major portion of recent cyber vulnerabilities are occurring due to a lack of input validation testing. Testing strategies should incorporate new techniques to account for the likelihood of input validation attacks. Structural coverage metrics allow us to see how much of an application is executed by a given test set. We have shown that the notion of coverage can be extended to target statements and their input values. Finally, we have answered our research question with a case study which demonstrates that using the technique we describe, it is possible to dynamically gather accurate coverage metric values produced by a given test set. We have shown that the notion of coverage can be extended to target statements, and we introduce a technique for manually determining this coverage value.

Future improvements can make these metrics portable to different database management systems as well as usable in varying development languages. We would eventually extend our metric to evaluate the percentage of all sources of user input that have been involved in a test case. We would like to automate the process of collecting SQL statement coverage into a tool or plug-in, which can help developers rapidly assess the level of security testing which has been performed as well as find the statements that have not been tested with any test set. This work will eventually be extended to cross-site scripting attacks and buffer overflow vulnerabilities. Finally, we would like to integrate these coverage metrics with a larger framework which will allow target statements and variables which are included in the coverage to be tested against sets of pre-generated good and malicious input.

9. Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation under CAREER Grant No. 0346903. Any opinions expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

9. References

- [1] B. Beizer, Software testing techniques: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co. New York, NY, USA, 1990.

- [2] S. W. Boyd and A. D. Keromytis, "SQLrand: Preventing SQL injection attacks," in Proceedings of the 2nd Applied Cryptography and Network Security (ACNS) Conference, Yellow Mountain, China, pp. 292-304, 2004.

- [3] B. Brenner, "CSI 2007: Developers need Web application security assistance," in SearchSecurity.com, 2007.

- [4] M. Cobb, "Making the case for Web application vulnerability scanners," in SearchSecurity.com, 2007.

- [5] W. G. Halfond, J. Viegas, and A. Orso, "A Classification of SQL-Injection Attacks and Countermeasures," in Proceedings of the International Symposium on Secure Software Engineering, March, Arlington, VA, 2006.

- [6] W. G. J. Halfond and A. Orso, "AMNESIA: analysis and monitoring for NEutralizing SQL-injection attacks," in Proceedings of the 20th IEEE/ACM international Conference on Automated software engineering, Long Beach, CA, USA, pp. 174-183, 2005.

- [7] W. G. J. Halfond and A. Orso, "Command-Form Coverage for Testing Database Applications," Proceedings of the IEEE and ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering, pp. 69–78, 2006.

- [8] Y. W. Huang, S. K. Huang, T. P. Lin, and C. H. Tsai, "Web application security assessment by fault injection and behavior monitoring," in Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on World Wide Web, Budapest, Hungary, pp. 148-159, 2003.

- [9] S. Kals, E. Kirda, C. Kruegel, and N. Jovanovic, "SecuBat: a web vulnerability scanner," in Proceedings of the 15th international conference on World Wide Web, Edinburgh, Scotland pp. 247-256, 2006.

- [10] G. McGraw, Software Security: Building Security in. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley Professional, 2006.

- [11] J. Offutt, "Quality attributes of Web software applications," IEEE Software, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 25-32, 2002.

- [12] E. Ogren, "App Security's Evolution," in DarkReading.com, 2007.

- [13] T. Pietraszek and C. V. Berghe, "Defending against injection attacks through context-sensitive string evaluation," in Recent Advances in Intrusion Detection (RAID). Seattle, WA, 2005.

- [14] F. S. Rietta, "Application layer intrusion detection for SQL injection," in Proceedings of the 44th annual southeast regional conference, New York, NY, pp. 531-536, 2006.

- [15] D. Scott and R. Sharp, "Developing secure Web applications," Internet Computing, IEEE, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 38-45, 2002.

- [16] Z. Su and G. Wassermann, "The essence of command injection attacks in web applications," in Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages, Charleston, SC, pp. 372-382, 2006.

- [17] H. H. Thompson and J. A. Whittaker, "Testing for software security," Dr. Dobb's Journal, vol. 27, no. 11, pp. 24-34, 2002.

- [18] D. Willmor and S. M. Embury, "Exploring test adequacy for database systems," in Proceedings of the 3rd UK Software Testing Research Workshop, Sheffield, UK, pp. p123-133, 2005.

- [19] H. Zhu, P. A. V. Hall, and J. H. R. May, "Software Unit Test Coverage and Adequacy," ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 29, no. 4, 1997.

11. End Notes

- http://nvd.nist.gov/

- In Figure 1, we counted the reported instances of vulnerabilities by using the keywords "SQL injection", "cross-site scripting", "XSS", and "buffer overflow" within the input validation error category from NVD.

- http://www.junit.org

- A cookie is a piece of information that is sent by a web server when a user first accesses the website and saved to a local file. The cookie is then used in consecutive requests to identify the user to the server. See http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2109.txt.

- http://sourceforge.net/projects/itrust/

- US Pub. Law 104-192, est. 1996.

- http://works.dgic.co.jp/djunit/

- For our case study, we used MySQL v5.0.45-community-nt found at http://www.mysql.com/